I voted yesterday. I am not a fan of “early voting” and consider it a prime illustration of the unserious times in which we live. Nevertheless, I took advantage of what I hope will be only a temporary loophole in election law in order to avoid the very real possibility that, by Election Day proper, I will have become too cynical to care to vote at all.

That may be an exaggeration. I have never considered myself a cynic. I like to think of myself as a realist, and American politics over the last two decades or so has been a most unfriendly place for realists who are not swayed by the bombastic rhetoric of politicians whose only goal is to get one more vote than the opposing candidate. The days of the Reaganesque landslide, when voters eagerly went to the polls to choose by an overwhelming majority one candidate who was clearly and unequivocally superior to the other, are a fast-fading memory. Of this bygone era, Bethel McGrew offers a thoughtful lament.

My parents cast their first votes for president in 1984. Ronald Reagan was the incumbent, and he would win reelection in a landslide. This was the year of the famous “morning again in America” ad, which cast a warm sunrise glow over the nation’s economic prospects. But for my parents, and for the evangelical Christian stock they came from, a vote for Reagan wasn’t just a vote for more jobs and lower taxes. It wasn’t just a vote for the practical consequences of a Reagan presidency. It was a vote for the man himself.

Evangelical Christians voting this year for Donald Trump make no pretentions about voting “for the man himself.” They are voting, precisely, for nothing more than “the practical consequences” of his return to the White House while “the man himself” has spent a considerable amount of political capital lowering the expectations for what those consequences might be. In the end, his simply not being Kamala Harris may be good enough to justify a pragmatic vote but it will not be good, neither for Christian voters nor for the country at large.

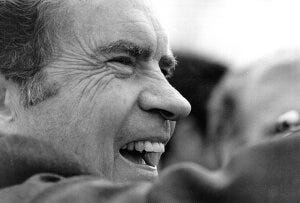

Bethel pines after the days of Reagan, as do I, but I am also not joking when I say that my respect and admiration for Richard Nixon, the president who set the pre-Reagan standard for landslide victories with his 1972 re-election, is growing with each passing day. It is easy to remember the ignominious end of his presidency in 1974, but far more difficult to remember the distinguished political career he enjoyed prior to his downfall. For all his faults, Nixon was a serious man who led during serious times. His personal religious beliefs were not particularly orthodox but, like his mentor and predecessor Dwight Eisenhower, he understood the importance of Americans sharing a common faith.

The Cold War was a dangerous time for America and the free world but, in retrospect, it may have actually been a safer time because the whole nation, for the most part, shared a common commitment not only to such political values as freedom and liberty but also to such spiritual values as virtue and a basic understanding of right and wrong. It wasn’t Christendom by any stretch, but it was a time when Christian values flourished in pursuit of the common good.

It wasn’t that long ago, really. Only half a century has passed since the Watergate scandal drove Nixon from office. Yes, a mere fifty years ago, it only took “a third-rate burglary” (as it was then described by Nixon’s press secretary) to bring down the most powerful man in the world. It would be very good, indeed, if only a handful of us should long for a time when so miniscule a matter so deeply offended the common decency of the populace.

In reality, it was a conspiracy to bring Nixon down.